Previous article:

Layers 3 and 4 are then “network” and “transport” layer, respectively.

While layer 1 and 2 had to do with local traffic, the next two layers create the standards and protocols by which all these local networks can talk to each other (“internetworking”). They scale to a global scale.

OSI Layer 3 – Network Layer

The network layer that currently dominates the world is the IP protocol. Nearly everyone has heard of an IP address by now, probably in frustration as they tried to configure a home device or internet connection.

The power of the IP protocol is in its superior route-ability. There have been other protocols that work well in certain circumstances, but IP proved to be the brilliant solution that literally created the internet.

IPs superior routability stems from it’s super simple addressing scheme, in which you take a bunch of numbers (an address), apply another set of numbers (called a mask) and end up with a neatly sliced network-host dileneation.

Photography: Yves Tessier 1972

You can think of the network as the street you live on, and the host as the house in which you live. In the following examples, the blue is the network/street, and the red is the host/house.

3472 Oak Street

10.29.44.6

But IP addressing is far more powerful than a street address, in that the networks can then further be sliced up using masks. A mask is another set of numbers that defines which part of the address is being addressed. So you could further say:

Cleveland, Ohio

10.28.44.6

Where orange is the locality and green is the larger area. This slicing can get even more granular and complex as needed.

I won’t risk complicating a simple and elegant system in trying to address it in one blog post. But the upshot is that millions of devices called routers can reliably and effectively transport huge amounts of data through multiple other routers and back. It’s not uncommon for traffic to go through 10-20 routers on its way to a destination.

OSI Layer 4 – Transport Layer

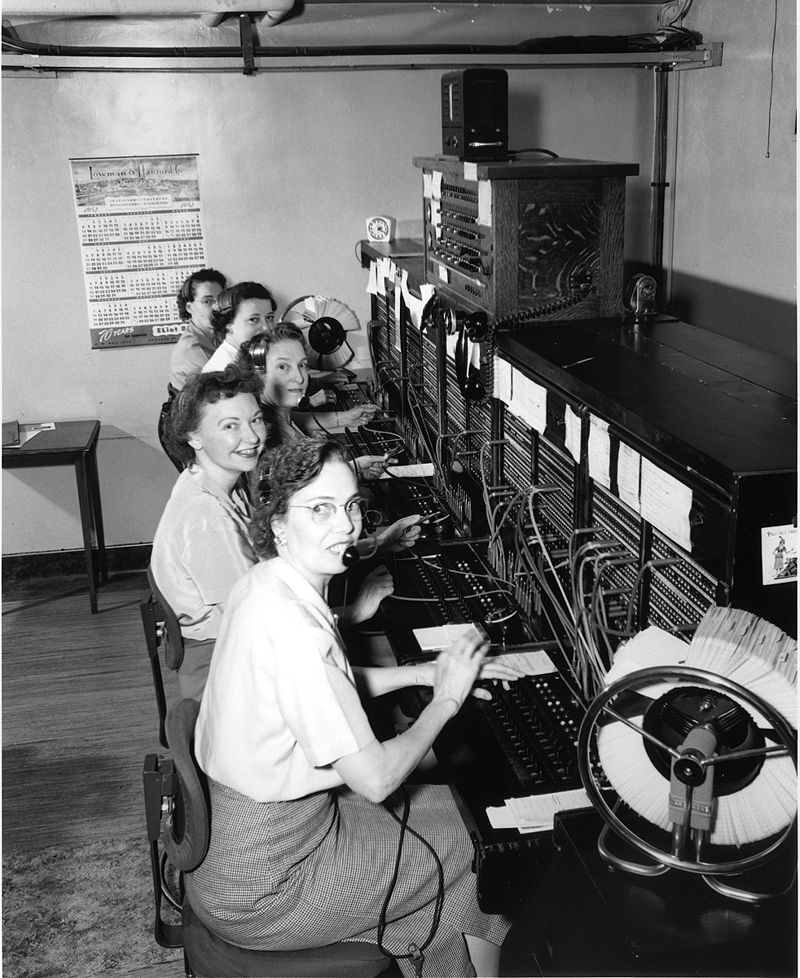

Layer 4 is the layer that defines a conversation. Take this human example of TCP (Transmission Control Protocol):

Sally: Hello is this joe?

Joe: Yes! This is joe.

Sally: Great! Here’s some info…..*garbled*

Joe: I’m sorry, can you repeat that? Also can you speak a little slower?

Sally: Sure…here…is….some…information…for you. Did you get that?

Joe: Yes I got it. I will deliver it to the appropriate party.

Src: Seattle Municipal Archives

This conversation is a representation of a TCP conversation that happens trillions of times a day. In contrast, here’s an example of UDP (User Datagram Protocol:

Sally: Hey, I’m shouting this to Joe! Joe, if you can hear me here some information for you!

Both of these conversations do essentially the same thing, but with a different set of requirements. These requirements are defined by a layer 4 protocol.

Across layer 3 and 4, there are several protocols and combinations of protocols that assist communication. They help control speed of transmission, choosing the best route between hosts, and several other critical functions that help ensure data gets from point A to point B.

Implications for Freedom and Democracy

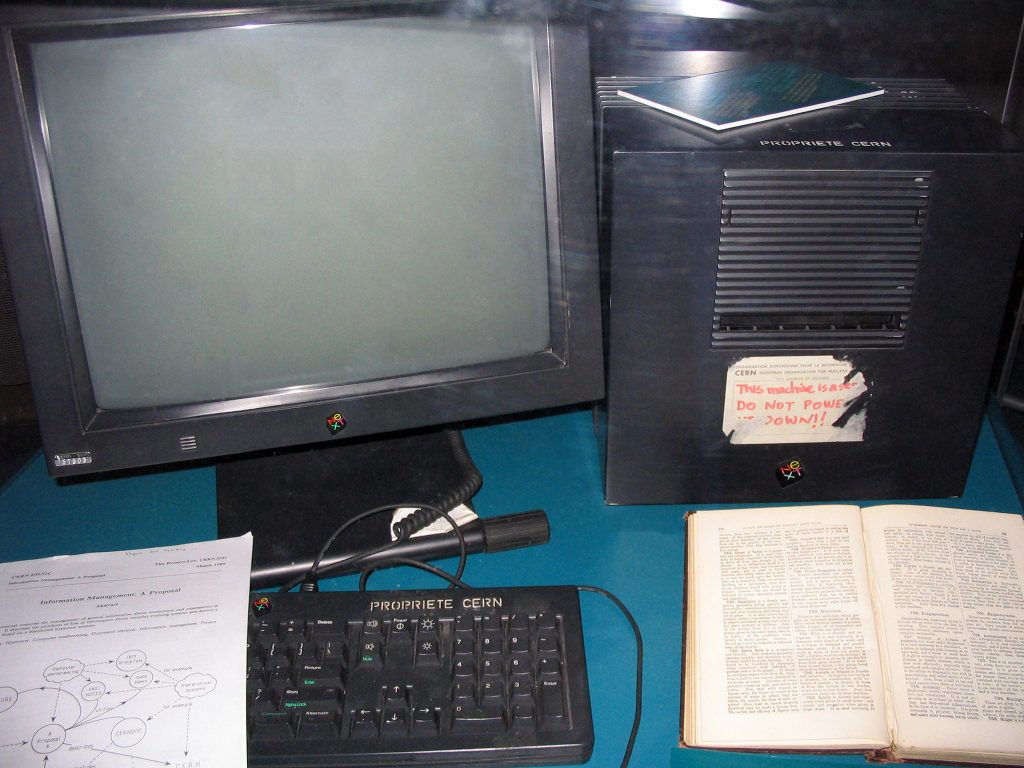

The creation of a redundant, reliable packet-switched (vs. circuit-switched) network of communications was created for two reasons. First, the number of computers in the world was very small, and people needed access to them without being physically present. Second, the military needed a way to maintain control of nuclear resources and communications in the even of a nuclear war.

These two goals are somewhat in dispute. And that makes complete sense given the supply of movie plots where scientific discovery was unwittingly being used for the military. It’s pretty obvious that everyone involved had their own goals in mind.

Src: Warner Bros

But, the implications for today are clear. Using these technologies, you can send data reliably from a very localized device to another very localized device anywhere around the world. We are seeing this play out now in Ukraine. This is a unique enough situation that I will post about it separately.

Because these systems were designed to create access via large scale, they ensure that anyone in the world can communicate with another. They can do this directly and without reliance on a mediator or central 3rd party.

Because these systems were designed, at some level, to survive nuclear hostilities, they are inherently robust and redundant. Getting in the way of these connections is very hard.

Freedom loves communication and the free flow of information. Indeed, it depends on it. Layers 1-4 are great enablers of freedom.

Next articles: